Paolo Erbetta Arte Contemporanea

Italy 71100 Foggia Via IV Novembre 2 +390881723493

http://www.galleriapaoloerbetta.it

info@galleriapaoloerbetta.it

19 december 2009 > 28 february 2010

curated by Nicola Davide Angerame and Paolo Erbetta

Opening Saturday 19 December 6:30 pm > 9:30 pm

Opening hours: Monday – Saturday 11 am – 1 pm / 5 pm – 8:30 pm Wednesday and Thursday by appointment

“It’s as if I had to read in photography the myths of the photographer, fraternizing with them, without believing too much”.

Roland Barthes, The Clear Room

The double solo exhibition at the Paolo Erbetta Gallery shows the recent works of Alessio Delfino (1976 Savona) and Chiara Coccorese (1982 Naples), two artists who “play” with photography in a literal and metaphorical sense: “literal” because both love to devote energies to the construction of their own sets; “metaphorical” because in this game with photography is the same photography to be put into play in its nature of objective reproduction of the real and becomes projection of the interior.

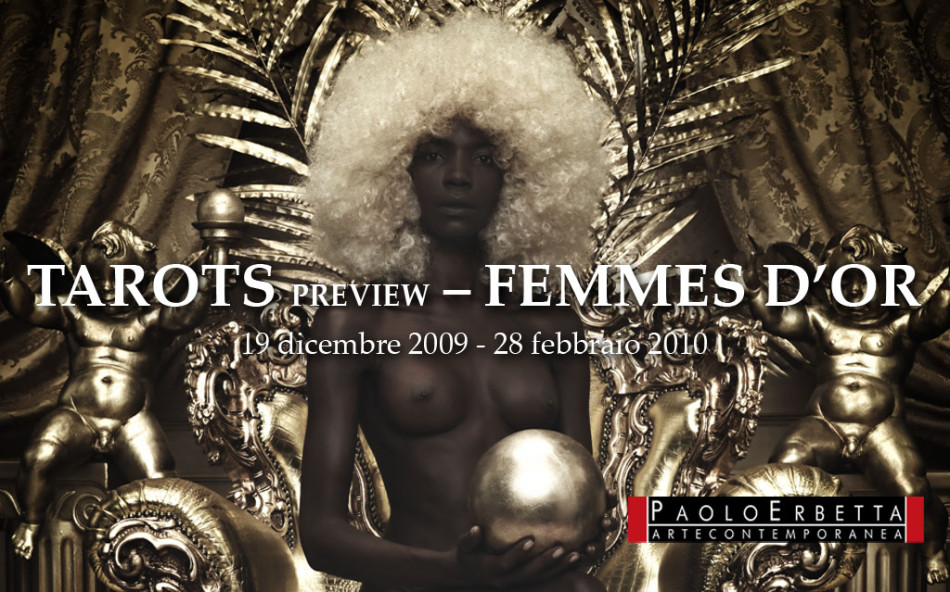

Tarots is the new photographic series by Alessio Delfino, dedicated to the representation of the twenty-two major arcana of the deck of the Tarot of Marseille, in the version commissioned in the first half of the fifteenth century by the Duke of Milan Filippo Maria Visconti which represents the highest expression of the tarot over the centuries.

In his work over ten years the young Savonese photographer has put at the center of his work the woman as an object of study. In the Tarots the strength of the symbol is intertwined with the seductive power of the body. The Empress is the first shot of this “wisdom” research that interprets tarot cards in a female version. Man is subject to destiny, just as he is to the eternal feminine, which overlaps him in a game of references. Le Diable sees a man subjected to the power of the mules. In a secular society marked by the exaltation of self made man, the idea of destiny has not followed much. Performing a pop operation, Delfino finds a way to talk about that “fate” that for centuries has represented a true cultural obsession for man. Without Fate there would be no ancient poems, Greek tragedy, astrology and much more, including the Tarot. Delfino’s Tarots’ femme fatale originated here. Using the neo-baroque style, Delfino’s photography speaks of a world understood as a “great representation” and of life as a path of subjection, more or less voluntary and conscious, to the power of the symbolic. He does this by combining some points of reference, from Erwin Olaf to Helmut Newton, passing through David lachapelle. If of the first, Delfino admires the vintage and elegant, evocative and mysterious atmospheres, the second appreciates the use of models with a post-feminist beauty, more aware and aggressive, decisionist, managerial, even sadistic. From the last, Delfino infers instead a certain taste for the game, for the wink and for a baroque that, if in lachapelle we know the well-known excesses ultrapop and mannerist, in Delfino remain subdued not to break the balance imposed by the seraphic afflato of the cards of destiny. A flatus voice, that of The Empress, bursting from a post-modern symbiosis in which photography exploits every possibility to create a space where the senses and symbols can hover with dramatic lightness, without losing the depth of an original feeling and without plunging into the obsolete splendors of rhetoric. As Roland Barthes points out in his book capital, for those who look “it is as if” should “read in the Photograph the myths of the Photographer, fraternizing with them, without believing too much”. Delfino’s photography produces such an effect of non-violent fascination, of playful seduction, of serious hilarity giving the image the possibility of being read on several levels.

In the previous series Femmes d’or, instead, Delfino matures an abstraction and dramatization of the nude. After dedicating two series to the transformation of the body in landscape and the transfiguration of the flesh in thin light writing, Delfino arrives at a series in which he uses golden body painting on non-professional models, to offer a different texture to the skin and set another relationship between flesh, light and photography. Trapped inside thick golden frames, daughters of a certain baroque taste for excess, these fragments of dancing bodies become voluptuous and dramatic objects. The ethereal consistency of the masses, the plasticity of the body volumes and the harmony of the forms determine a sculptural photography, in which the body takes on a spiritual value. The body fragment allows to better grasp the expressiveness of the whole, keeping at a good distance the eroticism, which Delfino remedies by “denuding the naked”, removing every sign and looking for a more authentic form of the body, a truer vitality.

If the world of Delfino is addressed to the suggestions coming from an ancient and disappeared world that believes in beauty as harmony and destiny as a “book” already written, that of Chiara Coccorese is instead addressed to another place of survival of the “myth”. It is a cozy and disturbing place which is that of the fairy tale. Thanks to a narrative approach to the stage photography genre, Coccorese reconstructs a world using the dreamy language of childhood. A stage of existence marked by a gnoseological approach to the game: building your own universe repeats the real one in order to make it familiar, playing as if that this could be available, tame. The mythologizing optic serves precisely to beautify and personify the “four seasons”, for example, in order to create an anthropological bridge with Nature indifferent to human destiny and pain, of which Giacomo Leopardi left an absolute testament in the Dialogue of Nature and an Icelandic.

In this reconstruction the artist is called into question through a work of mirrors reflecting his own image. Conceptual aspect of a photograph that provides a surreal vision, fun and fun, but seeks a contact with the most ideal aspects of photography: the authorship, the relationship between the subject and the object of photography, the presence of the author in the work. As Diego Velàzquez’s auroral masterpiece, Las Meninas, has taught us, the author of the work can become part of it through a gaze that makes his authority evident. Coccorese does so in Autumn, where she stages a female character immersed in a scene of autumn flavor. The backdrop is painted, the trees are made of fruits and berries, the soil is populated with dry leaves and nuts the woman is made of woods. Everything is fake because it’s true. The idea of the puppet is here put at the center of a game of which the author is the deus ex machina, the designer of a scenography that possesses the characters of a narrative that leads nowhere, as a fairy tale just mentioned to read in depth, as the crucified Scarecrow, rather than in chronological relaxation. We expect a story, but the works of Coccorese are linked to a visionary that opens a dimension of narration that connects the anxieties of the dream and the simplicity of the story to a certain childhood symbolism. Coccorese illustrates the chapters of a narration that unfolds like a dream, like a deconstructed fairy tale, in which the characters and landscapes are no longer together but go each on their own. A world of colors as in the Chocolate Factory directed by that Tim Burton to whom Coccorese could be indebted, if only his work leaned decisively towards the direction of the grotesque instead of opting for a more genuine dramatic and playful vein that brings it closer to the theater of Italian masks and that in the Neapolitan tradition can be so rich in colors and characters.

Coccorese’s photography starts from where Andy Warhol finished and from that awareness that stage photography has matured, confirming the artists’ intention to photograph worlds created by themselves. The end of the image “by excess of images” prophesied by Warhol, who screen-printed photos “stolen” to the media, leads to the end of photography designed as a tale of reality and gives birth to a new world that well described a “photographer juggler” like Vik Muniz, using the maxim: “There’s nothing left to photograph. If you want to photograph something new, you must first create it”. It’s the birth of a photograph that records a world created specifically for you, often for a single beat of your shutter.

Nicola Davide Angerame

Paolo Erbetta Arte Contemporanea

Italy 71100 Foggia Via IV Novembre 2 +390881723493

http://www.galleriapaoloerbetta.it info@galleriapaoloerbetta.it

19 december 2009 > 28 february 2010

curated by Nicola Davide Angerame and Paolo Erbetta

Opening Saturday 19 December 6.30 pm > 9.30 pm

Opening hours: Monday – Saturday 11 am – 1 pm / 5 pm – 8:30 pm Wednesday and Thursday by appointment

“It’s as if I had to read in photography the myths of the photographer, fraternizing with them, without believing too much”.

Roland Barthes, The Clear Room

The double solo exhibition at the Paolo Erbetta Gallery shows the recent works of Alessio Delfino (1976 Savona) and Chiara Coccorese (1982 Naples), two artists who “play” with photography in a literal and metaphorical sense: “literal” because both love to devote energies to the construction of their own sets; “metaphorical” because in this game with photography is the same photography to be put into play in its nature of objective reproduction of the real and becomes projection of the interior. Tarots is the new photographic series by Alessio Delfino, dedicated to the representation of the twenty-two major arcana of the deck of the Tarot of Marseille, in the version commissioned in the first half of the fifteenth century by the Duke of Milan Filippo Maria Visconti which represents the highest expression of the tarot over the centuries. In his work over ten years the young Savonese photographer has put at the center of his work the woman as an object of study. In the Tarots the strength of the symbol is intertwined with the seductive power of the body. The Empress is the first shot of this “wisdom” research that interprets tarot cards in a female version. Man is subject to destiny, just as he is to the eternal feminine, which overlaps him in a game of references. Le Diable sees a man subjected to the power of the mules. In a secular society marked by the exaltation of self made man, the idea of destiny has not followed much. Performing a pop operation, Delfino finds a way to talk about that “fate” that for centuries has represented a true cultural obsession for man. Without Fate there would be no ancient poems, Greek tragedy, astrology and much more, including the Tarot. Delfino’s Tarots’ femme fatale originated here. Using the neo-baroque style, Delfino’s photography speaks of a world understood as a “great representation” and of life as a path of subjection, more or less voluntary and conscious, to the power of the symbolic. He does this by combining some points of reference, from Erwin Olaf to Helmut Newton, passing through David lachapelle. If of the first, Delfino admires the vintage and elegant, evocative and mysterious atmospheres, the second appreciates the use of models with a post-feminist beauty, more aware and aggressive, decisionist, managerial, even sadistic.

From the last, Delfino infers instead a certain taste for the game, for the wink and for a baroque that, if in lachapelle we know the well-known excesses ultrapop and mannerist, in Delfino remain subdued not to break the balance imposed by the seraphic afflato of the cards of destiny. A flatus voice, that of The Empress, bursting from a post-modern symbiosis in which photography exploits every possibility to create a space where the senses and symbols can hover with dramatic lightness, without losing the depth of an original feeling and without plunging into the obsolete splendors of rhetoric. As Roland Barthes points out in his book capital, for those who look “it is as if” should “read in the Photograph the myths of the Photographer, fraternizing with them, without believing too much”. Delfino’s photography produces such an effect of non-violent fascination, of playful seduction, of serious hilarity giving the image the possibility of being read on several levels. In the previous series Femmes d’or, instead, Delfino matures an abstraction and dramatization of the nude. After dedicating two series to the transformation of the body in landscape and the transfiguration of the flesh in thin light writing, Delfino arrives at a series in which he uses golden body painting on non-professional models, to offer a different texture to the skin and set another relationship between flesh, light and photography. Trapped inside thick golden frames, daughters of a certain baroque taste for excess, these fragments of dancing bodies become voluptuous and dramatic objects. The ethereal consistency of the masses, the plasticity of the body volumes and the harmony of the forms determine a sculptural photography, in which the body takes on a spiritual value. The body fragment allows you to better grasp the expressiveness of the whole, keeping at a good distance eroticism, which Delfino remedies by “denuding the naked”, removing all signs and looking for a more autthentic form, a truer vitality.

If the world of Delfino is addressed to the suggestions coming from an ancient and disappeared world that believes in beauty as harmony and destiny as a “book” already written, that of Chiara Coccorese is instead addressed to another place of survival of the “myth”. It is a cozy and disturbing place which is that of the fairy tale. Thanks to a narrative approach to the stage photography genre, Coccorese reconstructs a world using the dreamy language of childhood. A stage of existence marked by a gnoseological approach to the game: building your own universe repeats the real one in order to make it familiar, playing as if that this could be available, tame. The mythologizing optic serves precisely to beautify and personify the “four seasons”, for example, in order to create an anthropological bridge with Nature indifferent to human destiny and pain, of which Giacomo Leopardi left an absolute testament in the Dialogue of Nature and an Icelandic. In this reconstruction the artist is called into question through a work of mirrors reflecting his own image. Conceptual aspect of a photograph that provides a surreal vision, fun and fun, but seeks a contact with the most ideal aspects of photography: the authorship, the relationship between the subject and the object of photography, the presence of the author in the work. As Diego Velàzquez’s auroral masterpiece, Las Meninas, has taught us, the author of the work can become part of it through a gaze that makes his authority evident. Coccorese does so in Autumn, where she stages a female character immersed in a scene of autumn flavor.

The backdrop is painted, the trees are made of fruits and berries, the soil is populated with dry leaves and nuts the woman is made of woods. Everything is fake because it’s true. The idea of the puppet is here put at the center of a game of which the author is the deus ex machina, the designer of a scenography that possesses the characters of a narrative that leads nowhere, as a fairy tale just mentioned to read in depth, as the crucified Scarecrow, rather than in chronological relaxation. We expect a story, but the works of Coccorese are linked to a visionary that opens a dimension of narration that connects the anxieties of the dream and the simplicity of the story to a certain childhood symbolism. Coccorese illustrates the chapters of a narration that unfolds like a dream, like a deconstructed fairy tale, in which the characters and landscapes are no longer together but go each on their own. A world of colors as in the Chocolate Factory directed by that Tim Burton to whom Coccorese could be indebted, if only his work leaned decisively towards the direction of the grotesque instead of opting for a more genuine dramatic and playful vein that brings it closer to the theater of Italian masks and that in the Neapolitan tradition can be so rich in colors and characters.

Coccorese’s photography starts from where Andy Warhol finished and from that awareness that stage photography has matured, confirming the artists’ intention to photograph worlds created by themselves. The end of the image “by excess of images” prophesied by Warhol, who screen-printed photos “stolen” to the media, leads to the end of photography designed as a tale of reality and gives birth to a new world that well described a “photographer juggler” like Vik Muniz, using the maxim: “There’s nothing left to photograph. If you want to photograph something new, you must first create it”. It’s the birth of a photograph that records a world created specifically for you, often for a single beat of your shutter.

Nicola Davide Angerame