It’s as if photography allows me to see the photographer’s legends, fraternizing with them but not quite believing in them.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida.

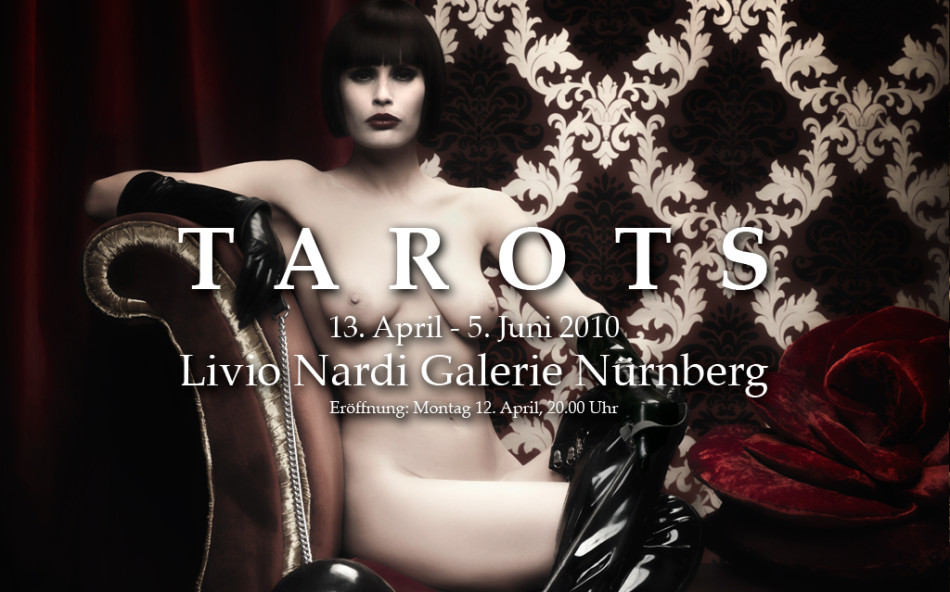

This new series, entitled Tarots, is a work-in-progress representing the twenty-two major arcana cards of the Marseilles tarot deck – the highest expression of which was perhaps the interpretation commissioned during the first half of the 15th century by Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan – used over the centuries for the esoteric divination of the destiny of men. The series opens with three pictures, meaning major arcana numbers XV Le Diable (The Devil), XVIII La Lune (The Moon) and XIX Le Soleil (The Sun) on display in gigantic dimensions in the entrance hall of the Gallery. Such stature is not a stylistic exercise but a declaration of subjection of the human being toward destiny and of the male toward the female. At least this is how the young artist from Savona considers the question of the eternal feminine: in his myriad of works Delfino has always made the woman an object of study, removing her from that context of explicit and consumerism-based desire to which she has been relegated by much of the photographic world. His exaltation of the feminine beauty and of the artistic nude, a genre that does not prevent him from achieving conceptual results, is functional to an undeclared and just as evident purpose if one is familiar with what has Delfino has created up to now: knowledge. It is not knowledge of beauty, of what is physical, of represented human bodies, but of an esoteric knowledge of the truth, of the authentic, of the origin. In this sense, Tarots is a noteworthy follow-up to the Goddesses of the Metamorphoseis series, exhibited in 2008 at the Rivara Castle during a personal exhibition in the stables area and now a permanent collection at the museum. In that series Delfino focused on pure physicalness, on the somatic traits of the feminine body from which one can deduce characters, personalities and temperaments. The artist assembled and combined them to create an interpretative “game” lying somewhere between everyday reality (that of the “models next door”) and the mythological figures of a Pantheon obsolete yet still active in our civilisation. This “game” brought into play an instinctual physiognomy, an “awareness of sensitivity” for which calling it intuition would be a tremendous oversimplification. It could be defined as an interior dialogue that seeks the meaning of a body, that of a model, that immediately becomes an expression of a “person”. Unconsciously assimilating the theories of the body of contemporary philosophy, Delfino introduces a key element into photography: that of knowledge understood as “relationship”. In the Tarots Delfino’s relational photography feeds on the relationship between the artist and the model in ways that are heterodox in respect to the “practice” of (advertising) photography that exploits the appearance of bodies. Delfino speaks to, is familiar with and listens to the deep aspirations of his women, then he works above it all, creating the most appropriate environment for them. The L’Imperatrice is the first example of this knowledge-based search linked to the world of the Tarot cards, a world that fascinates the artist because of its revelatory power, not of an objective reality but of a universe of symbols that refer to interiority and sensitivity. In the same manner that the world is “representation”, even the life and destiny of men are subject to the power of the symbolic. The major arcana with which Delfino maintains an iconological interpretative dialogue are the Marseilles tarot cards. If in Metamorphoseis he used the neutral pose and sequential nature to create a seraphic classicism, in Tarots the result is more refined and leans toward plasticity. Delfino welcomes the demands of the Tarot cards using certain inspirations and atmospheres of specific points of reference, meaning Erwin Olaf, Helmut Newton and David LaChapelle. If Delfino admires the first’s vintage, elegant, evocative and mysterious atmospheres, he appreciates the second one’s use of models with post-feminist beauty and heightened awareness, with aggressive, decisive, managerial and even sadistic features. For the last reference, Delfino assumes instead an evident gusto for playing, mischievousness (barely touched on in the appropriation) and a Baroque mannerism that if the end result in LaChapelle is the celebrated ultra-pop and mannerist excesses, in Delfino it remains subdued to avoid upsetting the balance imposed by the seraphic inspiration of the cards of fate. A flatus voci, that of the L’Imperatrice, that bursts from a post-modern symbiosis in which senses and symbols waft with dramatic lightness, without losing the depth of an original feeling and without plunging into the outdated pomp of rhetoric. As pointed out by Roland Barthes in one of his fundamental books, for the observer “it is as if” photography “allows him to see the photographer’s legends, fraternizing with them but not quite believing in them”. Delfino’s photography produces exactly such an effect of non-violent fascination, of playful seduction, of serious hilarity, allowing the image to be interpreted at various levels, thus stratifying its meaning and showing that photography is capable of combining glamour and suspense. As if beauty was merely the mask of a deeper truth. The L’Imperatrice is the first result of such a concept and is the first portal into the work of one of Italy’s most interesting new generation photographers.

Nicola Davide Angerame